late mediaeval sculptures

origin: church of Petrus, Zuidbroek, Groningen (NL)

date: 1500 – 1525 AD

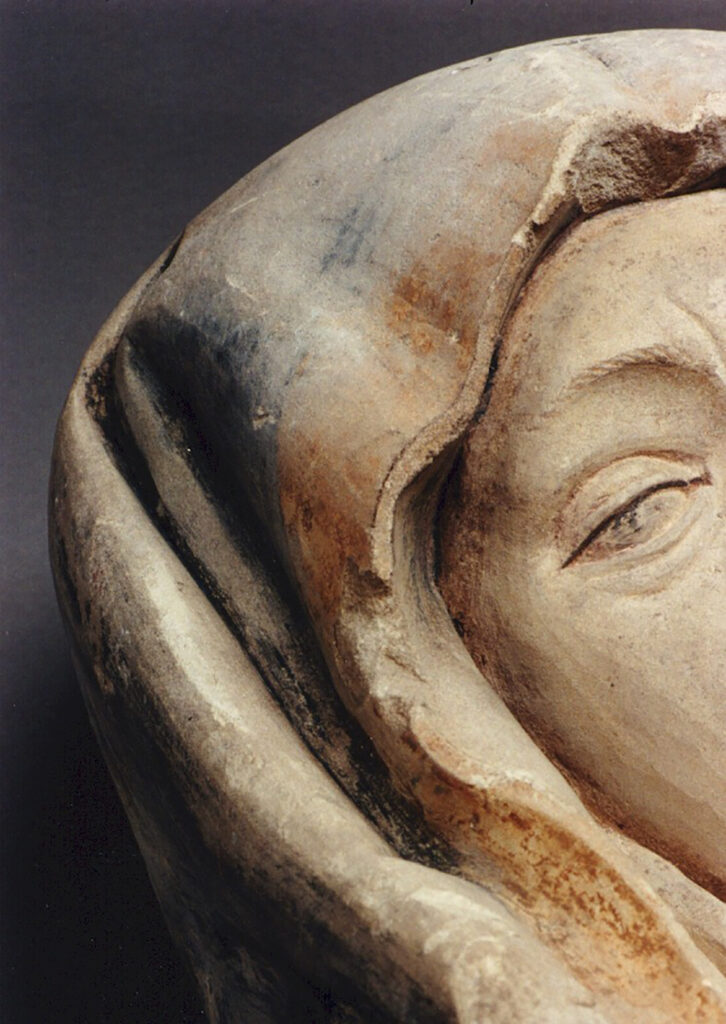

In 1997 the Petrus Church of Zuidbroek (Groningen, The Netherlands) underwent restoration. During excavation work at the outside of the building, the remains of life-size late mediaeval sculptures were found. The fragments belonged to one group of statues: head and shoulders of Mary as Mater Dolorosa (figures 1 and 2), and the torso and head of Christ. Not many mediaeval sculptures have been preserved in the province of Groningen. The well-known examples have been characterized as ‘provincial and primitive’1. Since the examples discussed here are of high quality, they are a valuable addition to the art history of the region2.

On the basis of Mary’s facial features and the presence of a crucified Christ, the fragments must have belonged to a ‘Calvary group’. Such a group usually consists of a crucified Christ in the center, with Mary on the left and John the Evangelist on the right (figure 3). The group takes its name from the mountain on which Christ was crucified.

Traces of polychrome are still present, which, especially on the bust of Mary, provide insight into the original painting. On the basis of the blue colour on the headscarf, Mary could be more precisely identified as a Maria Dolorosa. Paint traces are mainly found in folds or concealed areas where physical damage is less likely to occur (figures 4-6). For example: in the eyes pinkish-red remnants can be found at the location of the tear glands; red flakes of paint are visible on the lips near the crevice; at the top of the face, on the border between forehead and headscarf, soft pink paint traces can be seen; in the large fold to the left of the face, in the kink at the level of the mouth, blue-coloured remains can be detected; on the back of the head there is a hole in which most of the surface is coloured blue; and in one of the folds to the right of the face there are small flakes of gold-coloured paint or perhaps gold leaf.

conservation: very modest treatment

The sculptures were brought to the LCM as part of an emergency operation. After securing the fragments, it became clear that the owner had no interest in a detailed research and thorough conservation treatment. Therefore, the fragments have undergone surface cleaning only. Dirt has been removed using soft brushes, cotton swabs and distilled water, without affecting the polychromic residues. The results of this operation as well as some observations are presented here.

Chemical and microscopic analysis of the type of stone has shown that the sculptures have been made from a sandstone containing lime. More specifically this may be Baumberger stone, which was widely used by sculptors in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries AD3.

The sculptures are severely damaged. This is mainly due to the destruction in the sixteenth century and the subsequent four-hundred-year preservation in the ground. However, some recent damage is related to the renovation around the church in 1997 and 1998.

Recent damage to the statue of Mary is visible on her forehead (figure 7). A stone chip in situ seems to come off. The area to the right of it and the right eyelid are already missing stone chips. Closer examination of this damaged surface gave rise to the assumption that the rock may contain soluble salts, which can be recognized as small white spots and stains on the damaged surface. A chemical test on a loose rock fragment from the base of the bust confirmed the assumption. In addition, the rock (in damaged areas where salt crystallization has taken place) shows signs of internal disruption on a microscopic level. The two fragments of the statue of Christ were found to contain soluble salts as well.

There are various types of salts in the soil, which are able to migrate in dissolved form. Due to fluctuations in humidity and temperature, and due to differences in porosity of the soil and the type of stone, some salts may crystallize and hydrate at a specific RH. The conditions of burial have led to the accumulation of salts in the sculptures. A cycle of salts hydration and crystallization in the stone, eventually leads to disrupture of the material on a microscopic level. This means that the rock might eventually disintegrate. Any acids present will accelerate this process, because the lime in the sandstone is chemically converted and loses its binding capacity4.

The soluble salts endanger the preservation of the stone. Therefore it is desirable to desalinate the fragments by means of active conservation, or – if active conservation is not applicable – to be strict in terms of passive conservation.

An active desalination treatment entails that the object will be gradually and completely immersed in a bath with distilled water. The crystallized water-soluble salts in the sculpture will slowly dissolve. By changing the water regularly, the salts will eventually be removed from the object. However, there is a drawback to such a treatment in this particular case: it is not unlikely that the scarce residues of polychrome will detach or even dissolve. In case of detaching polychrome, complete immersion of the sculptures may be replaced by a repeated application of poultices to slowly distract disolved salts. Compared to immersion this might lead to a lenghty time span of treatment as well as an incomplete removal of salts. Another option is the fixation of polychrome residues by means of a permeable layer preceding the immersion treatment. This of course creates challenges on the choice of a water-immersion-suitable polymer as well as its reversibility. Unfortunately there was no posibility to test the condition or solubility of the polychrome remains, nor could the sculptures be treated to avoid further salt related damage.

A (temporary) solution should be found in passive conservation. The sculptures could be placed in a room or showcase with climate control, in which the process of crystallization – (partial) dissolution – recrystallization can be prevented by maintaining a dry and stable climate with an RH close to 55%. In the longer term however, it is desirable to desalinate the sculptures, finding a method that is not destructive to polychrome.

Even after the desalination treatment, placement and exhibition in a regulated environment is desirable because the church space itself has no stable climate. Furthermore it is necessary to take into account the lighting; this must not lead to a discoloration of the polychrome.

1 see Bouvy

2 see Van Weezel

3 see Karrenbrock

4 see for example Paterakis

further reading

- Bouvy, D.P.R.A.; Middeleeuwsche Beeldhouwkunst in de Noordelijke Nederlanden, Amsterdam, 1947

- Karrenbrock, R; ‘Kleinodien aus Westfalen, versandt über das Meer. Bildwerke aus Baumberger Sandstein und ihre Bedeutung für den Hanseraum’, in:Westfalische Steinskulptur des späten Mittelaters 1380 – 1540, cat. tent. Unna (Evangelische Stadtkirche Unna) 1992

- Van Weezel Errens, D. en Molema J.; Een Calvariegroep op het kerkhof van Zuidbroek, Groninger Kerken, 16e jrg nr. 2, juni 1999, 7-15

- Paterakis, A.; Deterioration of Ceramics by soluble Salts and Methods for Monitoring their Removal. In: Black, 1987, 67-72. Black, J. (ed.), Recent Advances in the Conservation and Analysis of Artifacts, Summer School Press, London, 1987.

1999 © GIA